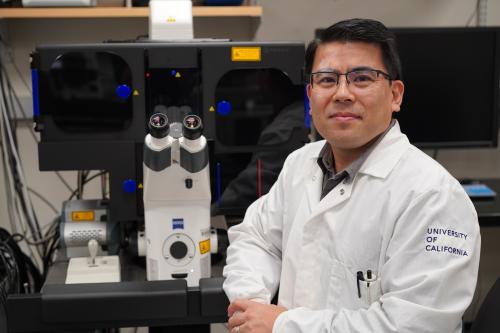

Under the microscope: Q&A with Microscopy Core Director Ken Yamauchi

As the microscopy core director at the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA, Ken Yamauchi, Ph.D., serves as a reliable resource for the core’s users. He identifies the most prominent needs of the core to make improvements that advance scientific research at the center.

Yamauchi, who earned his doctorate in neuroscience from the University of Southern California, loves to see the way small things can form part of a larger system. This has been a pattern in his life ever since a simple eighth-grade experiment sparked his interest in microscopy and biology. Here, he talks about his vision for the microscopy core, the crucial ways core resources advance science and his hobbies outside of the lab.

How did you first become interested in microscopy?

I had the chance to use a confocal microscope for the first time during graduate school, but the actual moment I became interested happened in eighth grade. I was taking a high school biology course and our assignment for the day was to take some water from a muddy field and look at the sample under a microscope. At the time, I remember thinking “What could we possibly learn from this?” When I looked through the microscope I could see hundreds of multicellular organisms moving and swimming around. That was my first introduction to microscopy and it was also the moment I fell in love with biology.

Why is microscopy important to science?

Microscopy lets you build a story and answer questions by allowing you to see details in a sea of information. For example, when using a microscope, you might want to look at the development of a cell's final form. The singular cell is hidden among many other cells that are doing their own thing, but with a microscope, you can follow that singular cell over time and you have the ability to pick out the details of what gives that cell its identity.

There are so many different types of microscopes: the simple compound microscope I used in eighth grade that allows users to see small organisms, electron microscopes that allow people to see the tiniest details and confocal microscopes that exclude out-of-focus light for sharp images, just to name a few. They're all important to advance our knowledge.

What do you like most about microscopy?

Microscopy allows you to see fine details you can’t assess with your eyes alone. Scientists are continuing to push the limits of what's currently possible and manufacturers are making cutting-edge technology available to researchers. It's amazing to me that some of the technology we use today wasn’t available just a few years ago. I find it exciting to be on the research side of these microscopy advances to better understand and help answer important questions in biology, health and disease.

I even see value in a poor image. I enjoy exploring the “how” and “why” an image was taken and figuring out what caused the “bad” image.

What’s your vision for the Microscopy Core?

The microscopy core has grown over the past decade. We initially started with four or five instruments and now we have 11 systems to cover most research needs. My goals are to provide more one-on-one training, help new and exploring scientists advance their research, create and participate in more educational seminars and provide a better user experience throughout the core.

We're going to do more than just troubleshoot. By facilitating open dialogue and collaborative discussions with core users and faculty, I want our users to feel well-trained and educated. I don’t want users to struggle to capture images, which can result in delayed scientific discovery and publications. We're going to consistently improve over time by identifying and meeting microscopy core user’s needs, keeping up with new technology as it becomes available and creating ways to make a positive impact throughout the center.

Why are core facilities so important for science?

Labs need equipment in order to advance their research studies. However, not all labs have access to expensive machines like our super-resolution microscopes. A core facility provides specific equipment for researchers without a large financial burden on the lab, as well as expertise for each piece of equipment.

My colleagues and I are constantly expanding our knowledge through training so we can improve the core experience for our users. Graduate students might not need every piece of information our microscopes offer, but we can help review samples and pinpoint any sort of analysis that needs to be done for their particular research needs.

What do you like to do in your free time?

I really enjoy taiko drumming. The form I use is called eisa and it’s native to the Okinawan islands. It's physically taxing, so I’ve since retired from playing after 20+ years.

These days, I enjoy tending to my garden and landscape, which includes a variety of flowers and shrubs. My wife and I also enjoy growing different vegetables and we recently planted some cherry blossom and Japanese maple trees.

What’s your guilty pleasure?

One of my guilty pleasures is watching shows that my wife finds silly. I tend to take over the TV to watch programs like “Forged in Fire,” “BattleBots” and “Antique Roadshow.”

If you could master one skill, what would it be and why?

At the moment, it'd be to become fluent in Japanese. I go to Japan every few years to visit my relatives, but whenever I visit, I struggle to communicate because my Japanese isn't very good. It’d be nice to do everyday activities with ease, such as reading menus, shopping and driving.

What’s the most valuable life lesson you’ve learned?

I’m not sure I can point to a most valuable lesson, but one that has helped me is knowing that I have control over my own happiness. I accept the difficulties that come my way and know that it’s all about how I react to the world around me.

I can get pretty frustrated in certain situations, but I try to stay conscious of that. Doing so helps keep my stress levels down and allows me to handle these moments appropriately.

What motivates you?

For me, it’s all about contributing to society. I want to use my talents and knowledge to help make other people’s lives better. Specifically, I know that I'm good with and knowledgeable about microscopes, and I want to pass those skills and knowledge on to others.

What show are you binge-watching right now?

I like the Star Wars franchise and just started watching “Andor” on Disney+. I'm about five episodes in right now and it’s very good, I highly recommend it. I feel like they’ve been reformatting Star Wars with shows like “The Mandalorian” and “The Clone Wars,” and “Andor” gives off a grittier feeling, which I appreciate.

What’s one thing you love about California?

I love the various food options. I grew up in Torrance, which is a hub for good Japanese food and breweries. Ramen, sushi, curry, yakitori (skewered, grilled meats and veggies), yakiniku (BBQ beef)… you name it, you'll find it and it’s all delicious. I also love the great selection of wineries and breweries California has to offer, and of course, the weather is incomparable. It's very temperate, not too hot and not too cold.

What would you be doing professionally if you hadn’t gone down your current career path?

Before college, I wanted to be a mechanical engineer and work in the robotics field. Then I got to college and took some classes that convinced me it wasn’t the road meant for me, so I decided to obtain a degree in molecular and cell biology.

If I wasn't in my current job, I'd probably still be in research doing benchwork because I like hands-on work and digging into tough questions in basic biology.

What's one of your favorite microscopic images and why?

I’ve made a habit of focusing on microscopic images as data and never really sought to capture something that I'd consider poster-worthy. However, I consider neurons to be beautiful and when I was looking through some old data, I came across this image of motor neurons and glia that I took as a post-doc in Ben Novitch’s lab. I recall when I was live imaging this culture of mouse stem cell-derived motor neurons, I could only see the neurons because they were fluorescing in green while a calcium indicator was slowly pulsing in red. What I couldn't see was the sea of glia that formed a layer under the motor neurons, which was only revealed later when I fixed and immunostained this culture. While I like the image itself, it also reminds me that being curious and asking the right questions can help reveal what is hidden in plain sight.