Better ‘mini brains’ could help scientists identify treatments for Zika-related brain damage

UCLA researchers have developed an improved technique for creating simplified human brain tissue from stem cells. Because these so-called “mini brain organoids” mimic human brains in how they grow and develop, they’re vital to studying complex neurological diseases.

In a study published in the journal Cell Reports, the researchers used the organoids to better understand how Zika infects and damages fetal brain tissue, which enabled them to identify drugs that could prevent the virus’s damaging effects.

The research, led by senior author Ben Novitch, could lead to new ways to study human neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders, such as epilepsy, autism and schizophrenia.

“Diseases that affect the brain and nervous system are among the most debilitating medical conditions,” said Novitch, UCLA’s Ethel Scheibel Professor of Neurobiology and a member of the Eli and Edythe Broad Center of Regenerative Medicine and Stem Cell Research at UCLA. “Mini brain organoids provide us with opportunities to examine features of the human brain that are not present in other models, and we anticipate that their similarity to the real human brain will enable us to test how various drugs impact abnormal or diseased brain tissue in far greater detail.”

For about five years, scientists have been using human pluripotent stem cells, which can create any cell type in the body, to develop mini brain organoids. But the organoids they produced have generally been difficult to use for research because they had highly variable structures and inconsistent cellular composition, and because they didn’t correctly mimic the layered structure of the brain and were too small — often no bigger than the head of a pin. They also didn’t survive very long in the laboratory and contained neural tissue that was difficult to classify in relation to real human brain tissue.

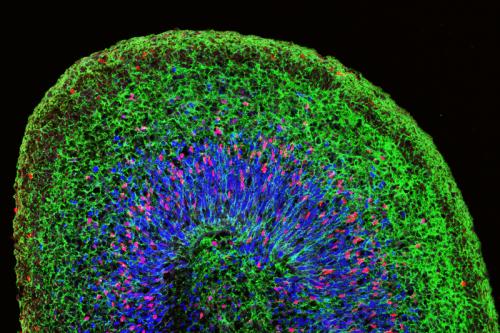

The organoids developed by Novitch’s group have a stratified structure that accurately mimics the human brain’s onion-like layers, they survive longer and have a larger and more uniform shape.

To create the brain organoids, Novitch and his team made several modifications to the methods that other scientists used previously: The UCLA investigators used a specific number of stem cells and specialized petri dishes with a modified chemical environment; previous methods used varying amounts of cells and a different type of dish. And they added a growth factor called LIF, which stimulated a cell-signaling pathway that is critical for human brain growth.

The researchers found critical similarities between the organoids they developed and real human brain tissue. Among them: The organoids’ anatomy closely resembled that of the human cortex, the region of the brain associated with thought, speech and decision making; and a diverse array of neural cell types commonly found in the cortex were all present in the organoids, and they exhibited electrical activities and network function, meaning they were capable of communicating with one another much like the neural networks in the human brain do.

The UCLA scientists also found that they could modify their methodology to make other parts of the brain including the basal ganglia, which are involved in the control of movement and are affected by neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease.

“While our organoids are in no way close to being fully functional human brains, they mimic the human brain structure much more consistently than other models,” said Momoko Watanabe, a UCLA postdoctoral fellow and the study’s first author. “Other scientists can use our methods to improve brain research because the data will be more accurate and consistent from experiment to experiment and more comparable to the real human brain.”

When the team exposed the organoids to Zika, they discovered specifically how the virus destroys neural stem cells, the cells from which the brain grows during fetal development. Novitch’s team found that there are four specific molecules, called receptors, on the outer surface of neural stem cells; previous studies have indicated that the Zika virus could bind to these receptors and infect the cells. The researchers then mapped the changes that occur in the neural stem cells after Zika infection, presenting a clearer picture of how the virus infiltrates and harms fetal brain tissue.

Zika is associated with an unusually high incidence of fetal brain damage, so understanding how neural stem cells are affected by the virus could be an important new step toward a treatment.

The researchers tested several drugs on the Zika-infected organoids. They found three that are effective at blocking the virus’s entry into the brain tissue, including two that protected neural stem cells by preventing the interaction between the virus and entry receptors on the neural stem cells. In previous studies by Novitch and other UCLA colleagues, one of those drugs reduced brain damage in fetal mice infected with Zika.

“Many neurological diseases or conditions arise from defects in the way one neuron communicates with another or from the way an external factor, such as a virus, interacts with neural cells,” Novitch said. “If we can focus in at the level of cellular communication, we should be able to model those undesirable cellular interactions and counteract them with drugs or other therapies.”

The team plans to continue using its improved organoids to better understand human brain development and to learn more about autism spectrum disorders, epilepsy and other neurological conditions.

The experimental drugs used in the preclinical study have not been tested in humans or approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating Zika in humans.

The research was supported by grants from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine and its California State University Northridge–UCLA Bridges training program; the National Institutes of Health; the Uehara Memorial Foundation; the Ministry of Science, Research and Arts of Baden-Württemberg; the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke’s Informatics Center for Neurogenetics and Neurogenomics; an UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center-Binder Family Foundation research award; and an UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center–Rose Hills Foundation research award.